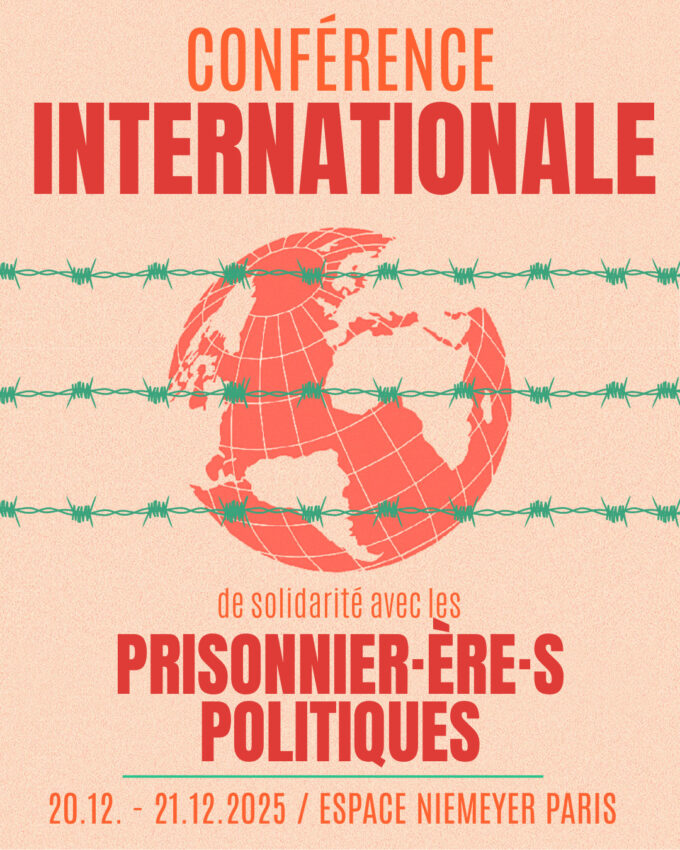

Political prisoners, political subjects (First contribution by the IRH to the International Conference in Paris for Political Prisoners)

Introduction

Imprisonment comes as no surprise to revolutionary, anti-colonial, anti-fascist or anti-imperialist activists. The timing and manner of arrest, the conditions of interrogation and detention, the terms of the trial and the severity of the sentence, etc. – all these factors are what give rise to unexpected circumstances. Neverthless, the prospect of being detained is something that activists must accept when they enter the struggle.

By being divorced from the street fighting, clandestinity, guerrilla warfare in the jungles, cities or mountains, and by being placed in a prison cell, activists are simply changing their position in the fight. While many people on the outside see this as a break, an upheaval (and this is all the more true for those who are less politically educated), activists see it as continuity – the continuity of their commitment.

Revolutionary prisoners can be divided in many ways: by their ideology and political project, by their country, by their conditions of detention, the length of their sentence, etc. But beyond all these differences, however important they may be, they are motivated by a common determination, which alone can explain their choices and positions. This determination is the will to remain political subjects.

It was with this understanding that Secours Rouge International was founded twenty-five years ago, bringing together forces supporting revolutionary prisoners from several European countries.

Symbols, willingly or unwillingly

Willingly or unwillingly, whether they are ready or not, political prisoners become symbols for both sides of the struggle. If the bourgeoisie manages to parade a repentant defendant, it considerably strengthens its power. On the contrary, if the masses perceive the accused revolutionaries as courageous, consistent and determined activists, the entire revolutionary cause is strengthened.

This “symbolic” status and the ideological stakes that accompany it are more or less significant depending on whether the enemy decides to impose a blackout or, on the contrary, to generate a media frenzy around the arrests, trials and/or detentions.

Experience shows that, generally speaking, the enemy gives a lot of publicity to arrests (which allow it to project an image of the omnipotence of its repressive apparatus), less publicity to trials (depending on a number of factors), and imposes a blackout on detention (political prisoners must “disappear” from society).

A four-pronged front

The prisoners’ determination to remain political subjects clashes head-on with the enemy’s determination. Indeed, the four objectives set by the bourgeois power structures in arresting and imprisoning revolutionaries are all aimed at preventing prisoners from continuing to contribute to the struggle.

These four objectives are:

1. Physically neutralise the revolutionary activist, i.e. prevent them from continuing their activism through imprisonment using physical force and confinement;

2° Imprisoning an activist and cutting them off from their organisation, preventing them from resorting to traditional forms of struggle, is not enough. Imprisoned activists can continue to carry out political work from within prison. The enemy therefore sets itself a second objective of politically and ideologically neutralising revolutionaries, for example by isolating them more or less radically from society, which explains why the imprisonment of revolutionary prisoners is generally associated with some form of solitary confinement.

3° Breaking the prisoner politically, making them renounce, if not their beliefs, then at least the revolutionary struggle, is the most radical and definitive way of achieving the first two objectives, with the added advantage that the broken activist provides information and often agrees to play a role in counter-revolutionary propaganda.

4° The enemy’s fourth objective is to intimidate society by instilling the idea that any revolutionary struggle is doomed to failure and imprisonment.

An imperative

The revolutionary imperative for prisoners is not to be objectified, turning them into victims of repression who plead for pity or compassion. They must become political subjects again, influencing events, transforming reality, calling for solidarity based on the fraternity of struggle. This is the primary motivation, the most decisive imperative.

The question that immediately arises for the detained activist is “how can I be useful to the struggle in this new situation?” Sometimes he or she is a member of an organisation (or tradition) that provides an immediate answer, sometimes he or she has to deduce it for themselves from their “here and now”.

The modalities

How can imprisoned activists contribute to the struggle?

1° First and foremost, by taking a position of resistance, i.e. refusing to collaborate or renounce their beliefs. It is important that this stance be public and demonstrative. If the position of resistance is known outside, it strengthens the cause. By showing themselves to be unbroken and unrepentant, prisoners erase the negative effect of the announcement of their capture and weaken the deterrent effect of imprisonment on the movement outside. By setting an example of resistance, they transform an event designed to demoralise the struggle into a reality that morally strengthens it.

2° Imprisoned activists also strive to become better activists. They read, study, educate themselves, learn foreign languages, etc. This explains why it is so important for them to receive books and newspapers, to be able to keep their notes, etc. They generally strive to maintain their physical condition and play sports.

3° Imprisoned activists use their time to read, reflect (and ideally discuss) in order to produce analyses useful to the struggle, assessments of their actions, explanations of their organisation’s policies, calls for mobilisation, statements of solidarity with other struggles, etc.

4° Imprisoned activists also confront the prison itself. This confrontation ranges from politicising a cellmate (and sometimes even guards!) to organising strikes, riots, prisoner unions, attacking or isolating informers, or simply showing solidarity (sharing food with destitute prisoners, etc.).

5° Finally, imprisoned activists fight for their release. Illegally, through escape, and legally, through interaction with lawyers and support forces, ensuring that these releases take place within a correct political framework (and not at the cost of a declaration of repentance, for example).

The means

It is by understanding this political and combative relationship to imprisonment that the forces supporting prisoners can understand what their own activity should be. Indeed, in order to fulfill one or more of these functions, imprisoned activists need two things: community and communication.

When activists are imprisoned in solitary confinement, or scattered across different prisons, etc., the issue of ending isolation is central. And even more so the rebuilding of a community of revolutionaries, because this multiplies the possibilities for prisoners to reflect and help others to reflect, to educate themselves and others, etc. Building a collective political life in prison is both an end in itself and a means to serve other ends.

Communication is understood in all its dimensions and in all senses. From the prison to the outside world, to communicate one’s thoughts and positions to the outside world; from the outside world to the prison, to receive information, books and documents that enable training, reflection and analysis; and from prison to prison, to enable links between prisoners, and first and foremost between political prisoners.

For these reasons, demands relating to communication and community are political demands in themselves; they do not fall under the categories of “comfort,” “well-being,” or “humanisation” of detention, etc.

For these same reasons, helping prisoners to ensure community and communication is a priority for political support forces such as the SRI. It is in this respect that this political support is specific and differs, for example, from the support provided by families or humanitarian organisations.

The enemy

As we have seen, when dealing with imprisoned activists, the authorities, in addition to managing the security concerns that apply to political prisoners (preventing riots, escapes, etc.), have a specific concern: preventing political “contagion” both inside and outside the prison. To this end, the authorities will tend to isolate imprisoned activists.

It is a zero-sum game: what one gains, the other loses.

The priority of one is the exact opposite of the priority of the other, and detentions are always a confrontation over these issues, the outcome of which depends on the balance of power – and thus also on the support that imprisoned activists receive from outside.

It is therefore on these issues, community and communication, that the struggles are most important and most difficult, and it is on these issues that the forces of support must focus.

And to wage this struggle effectively, it is necessary to have a good understanding of the enemy and to avoid two opposing errors:

– Overestimating the way in which the enemy plans detention; One must imagine a group of decision-makers and specialists scientifically developing a programme that impacts every detail of prisoners’ lives in order to destroy their political consciousness. The enemy is also a huge bureaucracy riddled with contradictions, career plans and departmental rivalries, mixing complete idiots with highly capable people.

– On the other hand, there is sometimes a tendency to underestimate this planning by attributing it to a “wicked manager” hostile to revolutionaries, or to a prison director who wants to preserve the tranquillity of his establishment by isolating potential troublemakers.

The reality lies somewhere between these two extremes, varying according to country, era and sometimes even prison. A thorough analysis of the enemy, their intentions and their resolve is therefore necessary.

Support

The first duty of those supporting imprisoned activists is therefore to recognise and respect their identity. This involves understanding their priorities in their demands and giving them the means to continue to act politically. It involves removing obstacles to this political activity (particularly solitary confinement), providing prisoners with political information, and relaying their messages.

Similarly, support for imprisoned activists should not be thought of as “first aid”. Prison itself is a battlefield, and this battlefield has direct repercussions and influences on the wider battlefields of struggle. Whether the struggle in prison evolves in one direction or another, the struggles outside will be strengthened or weakened.

Every liberation struggle goes through cycles of “struggle/repression/resistance to repression”. The ability of the forces of liberation, both inside and outside prison, to emerge victorious and stronger from the third phase of the struggle is crucial to the future of the process. And imprisoned activists play a central role in this phase.

Unity

Outside prison, revolutionary, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist and other revolutionary movements are generally fragmented into different forces, tendencies, political and strategic proposals. But when it comes to confronting repression as imprisoned activists, a tendency towards unity quickly emerges, both within prisons and among support forces. The terrain of struggle is simplified, choices are less complex than outside, “opportunities” for disagreement are fewer and the reasons for fighting together are more numerous and more obvious.

This explains why the struggles of imprisoned activists (and, outside, the support for these struggles) are at a higher level of unity than other fronts of struggle. Prisoners thus play, by virtue of their objective situation, a catalytic role in moments of unity, in processes of rapprochement between forces on the outside. This is an important and valuable political characteristic of the struggle of imprisoned activists that both prisoners and the forces supporting them must understand and value.

Of course, every revolutionary force, in order to be consistent, must have its own political line and strategy. It must defend them in debates and apply them with the utmost determination.

But at the same time, revolutionaries must welcome with interest and goodwill the existence of other strategic proposals, and even more so, they must integrate this factor into their strategic analysis.

Several historical episodes in the past have seen revolutionary forces clash militarily because the strategy of one hindered the strategy of the other. Each was convinced that its choices were the only valid ones, that the choices of the other would lead to the failure of the revolution, and that the use of force was legitimate and revolutionary. The revolutionary movement has lost a great deal as a result of this logic of the ‘objective enemy’.

We are not saying that such episodes are always avoidable; that it is only a matter of goodwill. We are saying that, when confronted with a heterogeneous revolutionary movement, revolutionary forces must strike a dynamic balance between three imperatives: defending and bringing to life their political and strategic proposals, working to the highest degree of unity possible with other forces, and confronting contradictions within the revolutionary movement in a non-antagonistic manner.

And resistance in prisons, such as support for revolutionary prisoners, is a front of struggle that allows different revolutionary currents to learn to fight together, to develop a unity of struggle in spite of their differences.